Could drones offer competitive advantage that draws new business? Yes, say these small business owners

Four years ago, Vadym Guliuk had little interest in drones. Then, clients started asking whether the Washington D.C.-based event photographer offered drone video service. Realizing there was a new demand, he bought a quadcopter equipped with a commercial-quality video camera, flight stabilization and collision avoidance technology. The price (including insurance, a commercial license and registration): about $2,200.

"It paid for itself in a day," he recalls. Guliuk estimates that half of his clients now ask for drone video. The best part: only 15 percent of his competitors offer drone service, which gives him a competitive edge in the market.

According to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), sales for commercial drones are expected to grow from 600,000 in 2016 to 2.7 million by 2020 opens in new window, and more businesses are finding creative ways to use them. Farmers and ranchers are sending drones up to keep an eye on herds and crops. Builders are using drones to conduct roof and other dangerous construction-related inspections on high-rise buildings. Amazon made its first drone delivery in the U.K. in December 2016. Small business owners like Guliuk are finding that these flying machines can offer competitive advantages if you know how to use them.

The Rules & Regulations

Drones — formally called Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS)—may look like toys, but search the phrase "drone accidents" online for the stories making serious headlines. There was the crash-landing of a drone in a no-fly zone near the White House in January 2015. Enrique Iglesias' hand was sliced by a drone during a concert in Tijuana, Mexico. In 2014, a photographer had the tip of her nose cut by a drone flying inside a chain restaurant. Accidents like these prompted the FAA to release regulations for commercial drone use in August 2016. Here are some of the FAA's Rules for operating a UAS.

FAA's Rules For Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) 2016

- Must have Remote Pilot Airman Certificate

- Must be 16+ years of age

- Must pass TSA vetting

- UAS must weigh less than 55 lbs.

- UAS weighing more than .55 lbs (250 grams) must be registered opens in new window

- Daylight-only operations, or civil twilight (30 minutes before official sunrise to 30 minutes after official sunset, local time)

- Maximum ground speed of 100 mph (87 knots)

- Maximum altitude of 400 feet above ground level, or within 400 feet of a structure

- No operations from a moving vehicle unless the operation is over a sparsely populated area

"Learn the rules and play by them," says Jake Butters, a Miami-based filmmaker who has logged hundreds of hours flying drones. Butters says he was one of the first operators to get a commercial license under the new rules, and notes that any business or individual hiring a drone operator for business should review the rules and regulations, too.

Flying over people, operating in controlled airspace without permission, and flying at night are potential violations that can lead to fines, or possibly even worse consequences, for commercial operators. Drone operators flying under the small UAS rule (drones under 55 lbs.) can apply for a certificate of waiver opens in new window, which allows operators to deviate from certain rules if the FAA deems it safe.

Get the Right Drone for the Job

"Safety is crucial," says Douglas Trudeau, a realtor in Tuscon, Arizona, who says he has been using camera drones for real estate since 2015. "Some cheap mall or truck stop drone isn't worth the money." Many commercial-quality drones come with flyer-friendly features like safe home return, steady hovering and collision avoidance. Along with the drone, controller and monitor, Trudeau recommends extra batteries, a carry case, density filters and several high-quality micro SD cards to get started.

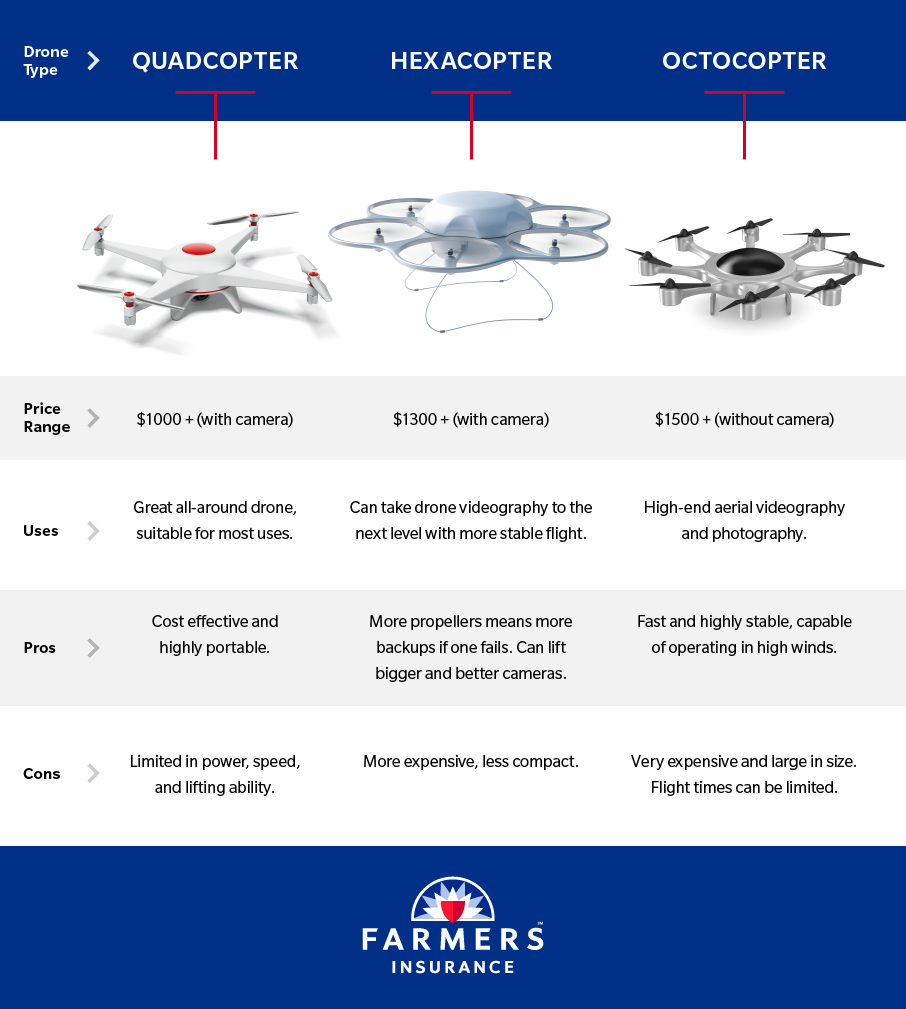

With dozens of commercial drones on the market, how do you choose the right one for your business? Unless you're long-distance flying (say, for inspection work in remote areas), professional drone operators like Butters and Trudeau fly multicopters, which come in several forms. These experts shared some potential pros and cons for would-be multicopter owners to consider.

There's More to Drone Service Than Flying

Trudeau says drone video service helped double his income last year, but he warns that bad drone footage is worse than no footage at all. If you're a pilot without much photography experience, Trudeau recommends hiring a skilled videographer who can also edit. "View their style, ask for references, and make an informed decision." Trudeau's real estate shooting tips:

- Focus on the home: "A lot of the video I see is excessive aerial video of the roof, the neighbors, neighborhoods, and the surrounding area, with little emphasis on the home itself," he says

- Keep it short: "A five- to 15-second aerial glimpse into the surroundings or to get a better angle of the home is all that's needed."

- Don't go too high: Shooting video more than 50 feet above ground level risks minimizing the home. Trudeau's "sweet spot": 20 to 30 feet up.

Drone, Drone on the Range

While snazzy aerial footage is in high demand, drone technology is finding a niche in other industries. Landon Smith, who grew up on a corn and soybean farm in Indiana, bought his first drone in high school after hearing a drone operator speak at a Young Farmers conference. "I flew a field for my grandpa, took 10 or 15 minutes of video, and we watched it together. We probably talked for over an hour about the history of that field," says Smith, recalling his first drone video flight.

Soon, he was offering mapping services to neighboring farms, where drones can capture everything from vegetation density to monitoring picking operations in remote fields. Smith sees drone use in agriculture getting even more sophisticated. "In the future, I think you'll have all of your different [drone] maps—population, feeding, time lapse—integrated in the tractor, and you can just pull up the images."

This aerial drone imagery of a field (top) demonstrates the flight path grid (middle) drone operators use to capture highly-detailed maps and models for businesses, including heat mapping, topography/elevation (bottom) and population density. Photo courtesy of CAVU Media.

How to Get Your Commercial Drone License

To get a commercial UAS license for work or business, operators must pass an aeronautical knowledge test at an FAA-approved knowledge testing center. Unlike automobiles or manned aircraft, there is no flying test requirement. (In other countries, such as Australia, drone pilots are required to pass a UAS flying test.)

Know Before You Fly opens in new window, an educational campaign from the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI), offers links in-person and online training courses.

To take the FAA's UAS drone exam, applicants must be at least 14 years old with a valid picture ID; to operate a commercial drone, pilots must be 16 years or older. Applicants must make an appointment at one of the FAA's testing centers opens in new window, pay $150, and pass the exam.

The two-hour pass/fail test test covers approximately 60 multiple choice questions; example questions are outlined in this sample UAS test from the FAA opens in new window. The minimum passing score is 70 percent.

The test questions cover:

- Regulations

- Airspace & Requirements

- Weather

- Loading and Performance

- Operations

After passing the test, licensed pilots can apply for a Remote Pilot Certificate, which requires a TSA background check. Upon passing the background check, a temporary certificate is issued before the FAA mails a final certificate.

Get some quotes for a drone operator

✔ 100% free service✔ Featured in the SMH, The Age & WA Today

✔ 1,800+ online recommendations